Writer & Photography / Sandy King

Most photographs are representative images that have a denotative or factual importance that gives preeminence to the signified (the referent in reality) over the signifier (the photograph). This is the ontological nature of photography and provides what most people expect from the medium.

The aesthetic and technical strategies of Pictorialism give more credence to the observance of truth to Nature than to the object in its world, demanding a reading on the level of signifier only. Thus, a gnarled and decaying stump of a tree is read not just as an object, but as its signifier, Nature, and perhaps even more, death and decay. Barthes refers to this kind of reading as an “obtuse meaning, outside of language, yet inside what we may call interlocution.”1

Definitions and Debate

What is Pictorialism? Mike Weaver offers an interesting definition, stating that the aim of pictorial photography is to “make a picture in which the sensuous beauty of the fine print is consonant with the moral beauty of the fine image, without particular reference to documentary or design values, and without specific regard to topographical identity.”2This is a definition of the picturesque, understood as an informal style that presents an embellished imitation of nature, generally free of man’s influence. The presentation of the picturesque is an important characteristic of Pictorialism. Other important qualities are: 1) an aesthetic concern with making art, as opposed to a record of the scene; 2) the concept that only images which show the personality of the maker, generally through hand manipulation, can be considered works of art; 3) an interest in the effect and patterns of natural lighting in the outdoor landscape; 4) an impressionistic rendering of the scene, in which overall effect is more important than detail; 5) the use of symbolism or allegory to reveal a message, and 6) the use of alternative printing processes: carbon and carbro, gum bichromate, oil and bromoil, direct carbon, and platinum.

From its earliest moments the parameters of photography have been defined by a debate about its very nature, pitting beauty for its own sake against utilitarianism, photograph as art against photograph as record, fact against fiction, the real against the ideal.

Two Competing Processes

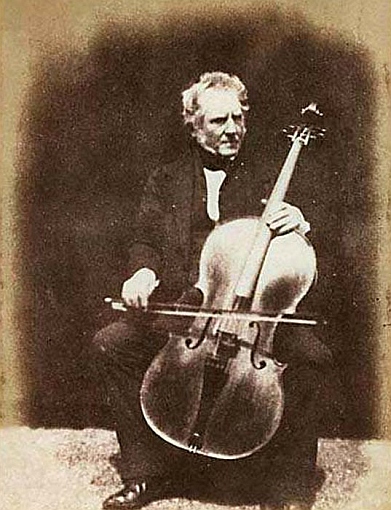

By an extraordinary coincidence of history, photography began with not one but two photographic processes, each very different from the other: the daguerreotype, capable of producing images with great sharpness and realism; and the calotype, which produces images with a softer, more painterly quality. In many ways these two photographic models have defined the antithetical purposes of the use of the medium. The sharp cutting image of the daguerreotype suggested the path of pure or straight photography, while the soft calotype seemed better suited for rendering the picturesque.

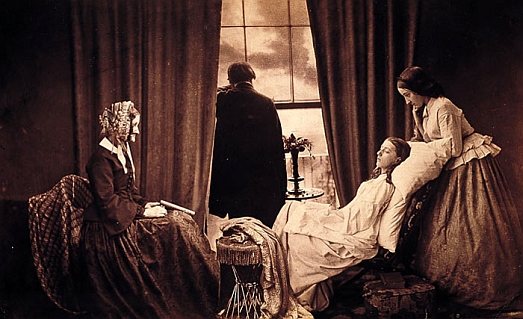

Pictorial Origins: Robinson and Emerson

As an artistic movement, Pictorialism has its ideological underpinning in the writings of Henry Peach Robinson and Peter Henry Emerson. Robinson developed the notion that pictorial photography was symbolic or allegorical at heart with his construct of “truth to nature” as opposed to “truth to facts.” In pictorial photography, symbolism may be merely ornamental, as in the depiction of nymphs in the woods, or allegorical in that the scene depicted has as its major purpose the revelation of a message. Thus, a ray of light represents purity or the divinity and a beautiful woman is a symbol of Beauty. Robinson published several books on photographic aesthetics, including PictorialEffectinPhotographyin 1869. In this book Robinson insists on truth to nature, which does not necessarily involve the strict observance of facts. For Robinson a fact is anything that exists, but truth is the absence of falsehood.

The school of Pictorialism, which was born in the late 1880s, adopted from previous generations the aesthetic of the picturesque, based in large measure on the theories of the Englishman Peter Henry Emerson, most succinctly expressed in his work Naturalistic Photography for Students of the Fine Arts, first published in 1889. Of the numerous concepts elaborated on by Emerson in Naturalistic Photography, two were critical to the development of Pictorialism: truth to nature, and the theory of tonal compression.

Emerson insisted on the concept of truth to nature, which for him meant that in art truth and fact are one. This concept represents an explicit rejection of the theoretical base of allegorical pictorialism as practiced by Henry Peach Robinson, who had earlier stated that “truth in art may exist without an absolute observance of fact.”3Emerson’s idea of truth to nature, in conjunction with the model of photography he offered in his book of photographs, The Life and Landscapes of the Norfolk Broad, steered Pictorialism toward the landscape as the preferred subject for the camera.

Emerson also defined the technical considerations of Pictorialism. Using a theory of human vision put forth by Ferdinand Von Helmholtz, he concluded that no art could duplicate the wide range of tones found in nature. This led him to suggest that the tonal values of photographs should be greatly compressed. To achieve tonal compression in his own work, Emerson used the platinum process, thereby establishing an important link between subject and process.

Lasting Influence

Although Emerson later renounced much of his own writings, his work had a profound impact on the British photographers George Davidson and Alfred Maskell. They began experimenting with a variety of printing techniques in an attempt to duplicate the soft tonal scale of Emerson’s platinum prints. Pictorialism as a movement was consecrated by an exhibition of the work of Davidson and Maskell at the Amateur Photography Club of Vienna in the summer of 1891. The hoopla surrounding this event established Pictorialism as the dominant tendency in art photography, a position it held in Europe and North America until the end of World War I.

The Importance of Manipulation

In the area of technique comma the use of alternative printing strategies that allowed manipulation of the final image was of the highest importance to the pictorialists. Technique is of paramount importance in the practice of photography, whether the final result is a record of the scene, or to make “art.” This has been true in all periods for pictorialists, who sought to convey an internal, subjective, vision, and for purists, whose goal was to discover, or merely record, reality. For the pictorialists, however, process was more important than verisimilar representation, and they often valued it for its own sake, because the most important consideration was not what the thing depicted, but how it filled the compositional space of the print. In essence, pictorialists were asserting the superiority of the conceptual ability of the photographer over the object and its place in the real world.4

The “Syntax” of Printmaking

Contemporary sensibilities emphasize photography as a creative activity separate from the constraints of the medium, but this attitude is overly restrictive. It is not possible to look at photographs as though they were ends without means, for every photograph is “the culmination of a process in which the photographer makes decisions and discoveries within a technological framework.”5The end result of the process is photographic syntax, which is determined by the chemical, optical and mechanical relationships of the medium.6The final stage in this process is printmaking syntax, which determines the final, tangible form of the image. At this stage, all elements of the object are important, for the color, texture, tonal scale, and reflective qualities of the printing material have a very real impact on the way content is expressed.7

The syntax of printmaking has been of absolute importance at every stage in the evolution of photography, though often its importance has been ignored or misunderstood. At no time, however, has printmaking syntax been more important or impressive than during the period of salon photography, because photographs were printed for display in exhibitions, rather than for reproduction in books or magazines.8The Pictorialists, perhaps better than any other photographic movement, understood the importance of the “original” and as a consequence “expended an enormous amount of energy searching for ways to give their prints maximum surface beauty.”9

Pigment Printing – The Enobling Process

The roots of all pigment printing processes go back to a patent taken out in 1855 by the Frenchman Alphonse Poitevin. In his patent, Poitevin described processes very similar to direct carbon and gum bichromate, as well as collotype and the oil and bromoil processes. The modern history of pigment printing began in the early 1890s, during the period of photographic impressionism. In 1890 George Davidson won the highest award at the Annual Exhibition of the Photographic Society of London with a pinhole photograph entitled AnOldFarmstead(Davidson later changed the name to The Onion Field).10The award led to a schism in the Royal Photographic Society between proponents of the old school, who believed in sharp focus and hard-cutting lenses, and proponents of the new school, who admired atmospheric effect and diffusion of focus. The immediate result was the formation of the “Linked Ring,” a group of photographers of the new school committed to the principles of pictorialism.

Although the pinhole camera gave the soft images desired by pictorialists, the photographer still had limited control of the final image. The pictorialists believed that a photograph could be judged by the same standards used to judge other pictures.11There was a prevailing belief that only hand-crafted photographs could be considered works of art. The platinum process, used by Emerson, was very popular with the pictorialists, but the process did not lend itself to intervention on the part of the photographer. What was needed was a flexible printing process that would allow physical intervention by the photographer, and control of the final image. As a consequence many artist/photographers began experimenting with alternative printing processes in order to achieve the kind of effect they equated with art. This led to wide-spread popularization of the pigment processes. The pigment processes were called the “ennobling” processes because they permitted the exploration of creative ideas by hand manipulation.

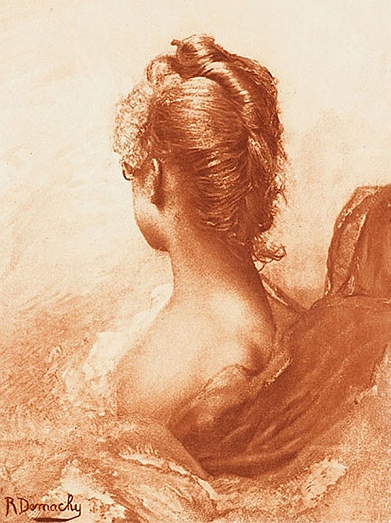

The pictorial use of the pigment processes began in 1894 when Rouillé-Ladevèze demonstrated to members of the Société Française de Photographie prints made with the gum process. That same year he published a book of the process, Sépia-photo et sanguine-photo.12 Gum printing was further popularized by Robert Demachy and Alfred Maskell.13Gum bichromate immediately became the preferred printing technique of pictorialists, a position it retained until replaced by the more flexible oil process in the early 1900s. Oil printing was introduced as a photographic process by G. E. H. Rawlings in 1904 and within a very short period of time eclipsed gum in popularity. Bromoil, a sister process to oil, was introduced by C. Welborne Piper in 1907.

Into The 20th Century

Although Pictorialism faded as a school by the end of World War I, pictorialism as a movement survived as an important photographic tendency until the 1930s, though with increasing opposition from advocates of straight photography, the so-called purists. The controversy between the pictorialists and the purists played itself out in a series of debates in the photography journals of the period, culminating in the 1930s in Camera Craft magazine with an exchange of articles between William Mortensen, the leading pictorialist of the day, and Ansel Adams, who defended the cause of straight photography.

The process of straight photography is very direct: be there, put the camera on a tripod, and photograph to reveal a maximum of information; then, process the image and make the final print to maximize tonal qualities and detail. The path of pure photography leads from the daguerreotype, through sharp-cutting collodion-based photography, to today’s glossy silver gelatin papers. Its practitioners through time have been Muybridge, O’Sullivan, Jackson, Ansel Adams, Weston, Strand, Atgeet, Renger Patsch, and numerous others. Though the ideological underpinnings of these photographers are different, all would share a common belief, best verbalized by Edward Weston and Paul Strand in the early 1920s: photography has certain basic qualities which, derived from its technical parameters, endow it with a specific mission and impose on it certain mechanical principles. Strand writes that there are laws to which we must ultimately conform or be destroyed, noting: “Photography, being one manifestation of life, is also subject to such laws. I mean by laws those forces which control the qualities of things, which make it impossible for an oak tree to bring forth chestnuts.”14

The Rise of “Straight“ Photography

The argument between the pictorialists and the purists was never really resolved, but Adams won a clear political victory. Straight photography became the accepted doctrine of the photographic art establishment, and the hated pictorialists were effectively banished from the civilized world of the new high priests. Nonetheless, all that was pictorial did not disappear with the dominance of straight photography. It is important to remember that the only major point of contention between the purists and the pictorialists was over process, not content or individual expression. Essentially, purists favored optical precision, and the use of purely photographic processes, while the pictorialists pursued their art through various manipulative printmaking processes. The landscape continued to be a major subject for purists, and the picturesque style continued to be dominant.

Edward Weston wrote: “I must conclude . . . that my ideals of pure photography . . . are much more difficult to live up to in the case of landscape workers-for the obvious reason that nature unadulterated and unimproved by man-is simply chaos. In fact, the camera proves that nature is crude and lacking in arrangement, and only possible when man isolates and selects from her.”15Moreover, the principles of pictorial composition continued in the documentary work of many photographers, including Dorothea Lange and Frank Eugene Smith, and even in Weston, who wrote: “A purist who is going to get any results has of necessity to know a great deal about composition. The manipulator can stick some clouds in a vacant sky, paint out a couple of houses, move the gate from the right to the left end of the wall, and remove the telephone wires to get his ‘composition’ right. But the Purist must do all this before he makes his exposure.”16

In Retrospect

However, even as a tendency, pictorialism did not altogether disappear after the 1930s. Many pictorialists continued to be active in the 1940s and 1950s, although ignored by most members of the fine art establishment. David Brooks has commented on the irony of this situation: “In the last few years retrospective portfolios have been published in popular magazines; exhibits have been mounted in important museums and galleries; works have been auctioned by the most prestigious agents; and the Library of Congress has issued silver and lithographic prints all involving photographers like Arnold Genthe, Gertrude Kasebier, Robert Demachy, Baron A. DeMeyer, F. Holland Day and William Mortensen. In their day each of these artists (a number of others, as well) created photographs that were hung in exhibits, published in magazines and journals, and purchased by museums. They were equally celebrated in time as many well-known photographers are today. How incredulous then that not one of these photographers is listed in the most important history of photography used in this country’s schools and departments of photographic education. In fact, Pictorialism-the philosophy and technique represented by these and many more photographers-is given only a few scant pages of begrudgingly condescending recognition in these histories, along with the impression that the movement atrophied and slipped into oblivion well before many of the individuals named produced their most significant work.”17

In retrospect, most of the criticisms leveled against the aesthetics and techniques of pictorialism have proven to be either erroneous or irrelevant to contemporary standards of photography. Since the late 1970s there has been a significant revisionist tendency toward Pictorialism among historians. This has resulted in the publication of numerous studies that affirm the historical importance and validity of the techniques and aesthetics of the movement, initiated by Peter C. Bunnell’s seminal edition of essays, APhotographicVision,PictorialPhotography,1889-1923, first published in 1980.

Renaissance in Alternative Processes

In terms of technique, the printmaking procedures of the pictorialists have also been validated by the criteria of contemporary art. Beginning in the late 1960s there has been an increasing interest in the importance of alternative photographic printmaking processes, beginning with the resurrection of pinhole photography, continuing with the photo silk-screen technique, culminating in the digitally manipulated imagery of the contemporary period. Paul Strand’s bold assertion on gum printing, that in the future “nobody will be willing to spend the time and energy or have the conviction necessary to the production of these things,”18proves that no artist, however talented, has a crystal ball.

Since the 1970s there has been a veritable explosion of interest in the processes of pictorialism, primarily platinum and gum bichromate, and more recently, oil and bromoil. Dozens of works devoted to alternative photographic processes have been published, including books on carbon, gum bichromate, oil and bromoil, gumoil, and platinum. Photographers known primarily for their work with the pigment processes include Sheila Metzner, Betty Hahn, Robert Fichter, David Scopick, and Stephen Livick, and platinum and palladium has witnessed a similar renaissance in the work of Dick Arentz, George Tice, and numerous others. In the light of contemporary art practice, Helmut Gernsheim’s description of pictorialism as a “hybrid arising from a misconception of function” seems curiously naive, if not altogether ridiculous.

Notes

1Roland Barthes, “The Third Meaning: Notes on Some of Einstein’s Stills,” Artforum (New York), vol. XI, no. 5, January 1973, 49.

2Mike Weaver, The Photographic Art: Pictorial Traditions in Britain and America (New York: Harper & Row, 1986) 8.

3Quoted in Margaret Harker, The Linked Ring (London: Heinemann, 1979) 29.

4Anthony Bannon, The Photo Pictorialists of Buffalo (Buffalo: Media Study, 1981) 29.

5William Crawford, The Keepers of Light: A History and Working Guide to Early Photographic Processes (New York: Morgan & Morgan, 1979) 6.

6Crawford, 5.

7Crawford, 14.

8Margaret Harker, The Linked Ring (London: Heinemann, 1979) 107.

9Crawford, 15.

10On pinhole photography, Davidson wrote: “It will certainly do most photographers good to produce a few pinhole pictures. If they are not warped by prejudice, or blinded by ignorance, they cannot fail to feel the advantage that frequently is gained by such diffusion of focus.” Quoted in Eric Renner, Pinhole Photography: Rediscovering a Historic Technique (Boston, London: Focal Press, 1995) 41-42.

11John L. Ward, The Criticism of Photography as Art (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1970) 4.

12Rouillé-Ladevèze, Sépia-photo et sanguine-photo (Paris: Gauthier-Villars, 1894).

13Robert Demachy and Alfred Maskell, Photo-Aquatint or the Gum-Bichromate Process (London: Hazell, Watson & Viney, 1897)

14Paul Strand, “The Art Motive in Photography,” quoted in Photography in Print, ed. Vicki Goldberg (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1981) 283.

15Peter C. Bunnell, ed. and introd., Edward Weston on Photography (Salt Lake City: Peregrine Books, 1983) 86.

16Bunnell, 85-86.

17David Brooks, “Neopictorialism,” Journal of American Photography January 1983, 14-15.

18Strand, 279.